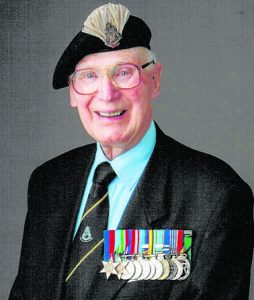

Colonel E. A. (Ted) White

1.2.1925 – 12.6.2021

From Trooper to Honorary Colonel of 10th Light Horse

|

Writing accounts of civilian soldiers must be prefaced by the fact that individual military stories are underscored by civilian life. Ted White is no exception. In the course of his military career he married, raised a family and at the same time progressed through the ranks of the Commonwealth Bank, eventually becoming a Senior Branch Manager in Perth and retiring as a Senior Administrator. Such dual roles in society are indicative of volunteer, civilian soldiers. Edward Astley White was born and raised in Western Australia. As a young man he enlisted in the Australian Army towards the end of the Second World War, where he rose to the rank of Sergeant in the Australian Intelligence Corp. He served in New Britain as well as with the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces in Japan. After the war Ted returned to the Commonwealth Bank and set out to extend his civilian career. When the Korean conflict developed in 1950, Ted was again attracted to the ranks of the Army. He relates that his mother was wise enough to say to him, “There’s going to be another war –for goodness sake go and get yourself a commission before it really starts.” Heeding this advice Ted presented himself to the 16th/28th Battalion, one of the local Citizen Military Force (CMF) infantry units and applied for reinstatement of his previous army rank with the view to gaining a commission. The response from the 16th/28th Commanding Officer was that even though he had been discharged as a substantive Sergeant, his background in the Intelligence Corp did not qualify him to be an Infantryman and, accordingly he was required to enlist with the rank of ‘Private’ if he wanted to join the Infantry. Ted agreed to do this and immediately enrolled in a non-commissioned officers’ (NCO) training course. Soon after he was transferred to the fledgling University Regiment of Western Australia and commenced preliminary officer training. Before he was able to complete this training Ted was transferred in his civilian job to the coastal town of Geraldton, north of Perth. Here his Army career received another set back. In Geraldton the local CMF unit had recently changed from an infantry unit to ‘C’ Squadron of the Tenth Western Australian Mounted Infantry (10 WAMI), which was an armoured corps unit. Even though he had completed a great deal of preparation as an Infantry NCO and was recommended for promotion to Corporal, events did not work out well for Private White. “I fronted up to the OC of ‘C’ Squadron, who told me that although I had a background in Intelligence and Infantry I knew nothing about armour and therefore I’d have to start off as a Trooper. I did this and in fact was drilled by Sergeants who hadn’t caught up with the latest drill manuals and alterations to drill — and were instructing us to do the wrong things. I had to put my finger in my mouth and just put up with it. Anyway within about two years I became a Lieutenant and that would have been about 1954.” At that time ‘C’ Squadron members were about 100 strong, a significant number for the size of the town, but the command structure was unbalanced. There were two Captains, no Lieutenants and a group of “very keen” Sergeants. Of additional interest was the presence of a number of ex-British Army NCO’s including an ex-Squadron Sergeant-Major, whose parade ground expertise was substantial, if not always accurate in terms of the latest manuals. The presence of such experienced personnel created expectations, down to the lowest levels of command, that being in the Civilian Army was not just a game. There were skills to be learnt and traditions to be upheld. The ethos of Light Horsemen of past eras was not far below the surface. Transferred back to Perth in his civilian employment in 1955, Lieutenant White continued his service with 10th WAMI. He became second-in-command of ‘B’ Squadron, initially under the command of Capt D. Cummuskey and later Maj T. Edmondson. This posting commenced an association with ‘B’ Squadron that was to last for over ten years. His return to Perth also coincided with another significant event in the history of the Regiment, the introduction of British-made Ferret scout cars as the main armoured fighting vehicle of the Regiment. Following the reformation in 1948, the Regiment was equipped with a make-shift establishment of vehicles. The main armoured vehicle was a cumbersome Canadian Scout Car, used as a reconnaissance vehicle and a Staghound Armoured Car, which supplied main armament fire-power through a 37mm cannon. When Ted White joined ‘C’ Squadron, the Squadron’s sabre troops were based on four vehicles, consisting of two Canadian Scout Cars and two Staghound Armoured Cars. As the Regiment’s tactical role and establishment emerged, military authorities decided that a dismounted capability was necessary to supplement the reconnaissance capability now assigned to the unit. Subsequently, ‘assault’ sections, based on the organisation of an infantry section were added to each sabre troop, and carried in a number of vehicles types, including the Whites Scout Car and a variety of soft skinned ‘B’ vehicles. Such vehicles were also used as command vehicles. In the early 1950’s the vehicle establishment began to change. The considerably more mobile British-made Ferret Scout Car was introduced to replace the aging Canadian Scout Car and a formal establishment of four Ferrets to a sabre troop was promulgated. One Staghound per troop was retained as the main armament vehicle and another British-made vehicle, the ‘Saracen” Armoured Personnel Carrier, was introduced to carry the troop’s assault section. With minor variations in vehicle numbers, and types, this organisation of six, all wheeled vehicles became the basic sabre troop composition for the next 15 years. The relatively spacious ‘Saracen,’ with appropriate modifications, also doubled as an effective command vehicle.

In the years that followed, Lieutenant White was promoted to Captain and assumed command of ‘B’ Squadron. He occupied this posting for the next ten years and, in retrospect, considers this time to be the most satisfying of his Army career. “I had a wonderful time – but the time I enjoyed more than anything was being OC ‘B’ Squadron, because, of course, you knew all your men intimately, down to every Trooper. You know the story! Recruits came in and you got to know them. You had much more intimate connection with everyone. In fact we socialised in one another’s homes from time to time, which was great, it built up wonderful esprit de corps with in the Squadron.” My personal association with Ted White began during the time that he was Officer Commanding (OC) ‘B’ Squadron. My first impressions were of a resolute, if not sometimes implacable Commander – and one incident in particular remains indelibly imprinted on my mind. This was an encounter during an annual camp in the Lancelin training area in about 1965. In the time that it took him to become OC ‘B’ Squadron, Ted White served under all Commanding Officers of the Regiment. As lavish as his appreciation is for these Commanders, and their different characteristics, he singles out particular attention for the professional dedication of Lieutenant-Colonel Dudley Cummuskey. Lt-Colonel Cummuskey had served as a Troop Leader in an Armoured Car Squadron in Italy during the Second World War and was a man of considerable Army experience. Lt-Colonel Cummuskey was Commanding Officer during the camp mentioned above and, as was almost characteristic of this Commander, the culminating exercise of the two-week annual camp involved a tactical operation in which the three sabre Squadrons of the Regiment were placed in highly mobile roles. In this exercise the two Perth sabre squadrons, ‘B’ and ‘C’ Squadron, advanced south along the main coast road that ran through the Lancelin training area. To call the thoroughfare at that time, a ‘road,’ might be somewhat of an exaggeration. In fact it was a narrow dirt track, pitted with limestone outcrops that could, and often did, easily disable wheeled vehicles such as those used by the Regiment. Against this advancing force was set ‘A’ Squadron from Northam as the “enemy.” About this time the French-made “Entac” guided missile system was in vogue and was considered to be one of the major threats to armoured vehicles at that time. To make the ‘A’ Squadron enemy vehicles more distinctive, simulated Entac systems were rigged up on the Mark 2 Ferrets. Used ammunition box were attached to each side of the vehicle turret and out of these protruded the nose cones of expended rocket propelled grenade projectiles. Added to this was a camouflage design created by spattering the vehicle with local mud and the result was a distinctive enemy vehicle. During the camp exercise, as Troop Leader of 3 Troop ‘A’ Squadron, I was given a task against the advancing Squadrons. I was to engage the advancing Troops at close quarters from ambush positions and as soon as they deployed was to retreat further south and repeat the process. To enable the advancing Troops to know they had been engaged and to add to the realism of an ambush, attached to the Troop was a Landrover towing a trailer on top of which was secured a 37mm cannon. This fired a blank round to simulate the ambush, a task very enthusiastically undertaken by Warrant Officer Allan Harris, who was Squadron Sergeant-Major of ‘A’ Squadron at that time. The result was not what I expected. During the proceedings the OC ‘B’ Squadron sat impassively on top of his command vehicle watching what we were doing. When I approached after the “shooting” had died down, he simply said to me, “Well done Sergeant,” and resumed the perusal of his maps. I was somewhat nonplussed. I had my Troop re-mount and moved back down the road from whence we had come, feeling somewhat deflated. Ted White was not prone to overuse superlatives! In 1967 Lt-Colonel I.D. Stock replaced Lt-Colonel Cummuskey as Commanding Officer of the Regiment, which had now been redesignated, ‘10th Light Horse.’ At about this time, Ted White experienced a growing realisation that to remain in his long-cherished posting of OC ‘B’ Squadron was becoming increasingly untenable. While Lt-Colonel Stock proved to be a most effective and popular Commanding Officer, he had been brought into the Regiment from the Engineer Corps, seemingly because there was no Senior Officer in the 10th Light Horse prepared to assume the task. Ted White considered it important that Armoured Corps ideals and expectations were reflected as much as possible in the upper echelons of the Regimental command and so, now a Major, he accepted a posting as second-in-command of the Regiment.

Ted White’s tenure as Commanding Officer of the Regiment lasted between 1970 and 1973, and spanned a period of intense social and military change in Australia. Perhaps the most significant of these changes were the cessation of fighting in Vietnam and a not altogether unrelated gradual decline in the fortunes of the 10th Light Horse as a full Regiment. It is also significant that during his tenure, Ted White orchestrated yet another change in vehicle establishment of the Regiment. By the end of his tenure the much-used and often maligned Ferrets had been replaced by tracked 1-1-3 armoured personnel carriers, these vehicles being viewed, at that time, as more appropriate for a modern Armoured Regiment. In May 1973, Lt-Colonel White was promoted to full Colonel and designated Commander of the 5th Military District Training Group. From there he retired from active duty on 31 December 1976. However, he had not yet finished with the 10th Light Horse. Shortly thereafter I had the honour to be made Honorary Colonel of the 10th Light Horse. I was Honorary Colonel from 1977 to 1981. So I had over 20 years active service with the Regiment, which probably would have been a record, I would think. Starting off as a Trooper and finishing up as the Honorary Colonel. What more can be said? In Egypt, before their embarkation to Gallipoli and again after their return to Cairo, the Australian Lighthorsemen were not renowned for their savoir faire in civilian circles. In the streets, bazaars and whorehouses of Egypt they created for themselves a reputation as being boisterous and rowdy as well as openly indifferent at times to all forms of rank and authority. A leaning towards improvisional larceny was certainly not confined to the non-commissioned ranks. Shortly after arrival in Egypt in 1915 the Australian Commander Harry Chauvel found that many of his horses had lost condition during the sea voyage from Australia and he set about culling large numbers of these animals. Chauval’s immediate superior, General Birdwood was alarmed at the number of culled animals and reduced it by three-quarters. As providence would have it, a few nights later a newly-arrived shipment of horses from Australia stampeded and scattered across the desert outside Cairo. Chauval and his men were assigned the task of rounding up the horses and when the task was completed the number of horses in need of culling in Chauvel’s Light Horse Regiments had dropped to almost nil, much to the disgust of a frustrated re-mount officer. In the latter-day 10th Light Horse Regiment there was no lack of such boisterous behaviour. In the early days of the newly formed Regiment, static camps were held in the army barracks at both Karrakatta and Northam. Often these locations were the scenes of rowdy and sometimes reckless behaviour, and it is not unfair to say that Ted White made his own contributions to such events. He was present when some of the almost legendary events occurred, outside the official military proceedings of the Regiment. From my earliest days in the Regiment I had heard stories of a Staghound main armament being discharged outside a mess window in one of these static camps. The story circulated around the campfires and messes for year, with embellishments and variations. But as Ted White relates, the incident did occur. It appeared that one night during an annual camp in the Northam Camp Area, the Officers of the Regiment, when Ted White was a Lieutenant, visited a nearby Gunners’ mess. On leaving for their own lines at the end of the evening, they found their Land Rovers had been filled to the roof with unbaled hay, with a note indicating that this was to feed their horses. The following morning a somewhat piqued Commanding Officer of 10th Light Horse, Lt Colonel K.D. Howard, commandeered a Staghound Armoured Car and crewing it with himself as crew commander, Capt B. Fisher, OC ‘A’ Squadron and the Adjutant, Capt T. Edmondson as gunner, directed the stunned driver, awed by the seniority of the crew, to drive the vehicle to the now empty Gunners’ mess and: “… put the 37 against the mess window and just let go [with a blank round]. Karumpa!! Of course it blew the bloody window straight out, there was glass everywhere.” The untold part of this story, and many others like it, is the money taken from the officers’ pays at the end of camp to make good the damage. Seeming indifference to superior rank is also evident in another of Ted White’s early experiences in the Regimental mess. This incident involved a visiting Brigadier who was heard to comment that the 10th Light Horse Officers’ mess was one of the quietest messes he’d ever been in. Apparently the estimation once again came to the attention of Lt-Colonel Howard who, one evening in the mess some time later, instigated a “game” called, ‘The Three Man Lift.’ In glib and deceiving tones Capt T. Edmondson cajoled the visiting Brigadier into taking part in an experiment to demonstrate how smaller men could lift a larger, more powerful man, which the Brigadier was. With one officer, Lt Pat Bowen pinning the Brigadier’s legs in prone position on the floor and Ted White holding firmly with linked arms back-to-back, Capt Edmondson calmly unzipped the victim’s fly and poured half a bottle of milk into the opening in the Brigadier’s dress uniform. “What was all that bull about?” demanded the Brigadier angrily as he struggled and tore loose from the men who held him. “Well the three of us got a ‘lift’ out of it, sir,” returned the nonchalant Capt Edmondson. Anyway he finished up taking it pretty well except that he really made a mess of my uniform. I had to take my blues home to my wife, my newly married wife and get her to repair them for the formal dining-in night back in Perth. The General had previously been warned that the Regiment was on hard rations and that meals would be somewhat rough. What the General was not aware of was that, through a number of contacts within the Regiment, the manageress and kitchen staff of the Lancelin Inn, a hotel located on the southern edge of the training area, were in the mess kitchen, using a Wiles cooker to convert available rations into special dishes. At another time I recall Lt-Colonel White monitoring the progress of a mobile exercise with an extension  lead and speaker from the radio in his vehicle, with the motor running outside a mess tent in the middle of nowhere, while he gave a running commentary to visiting officials inside the tent. I also remember, on more than one occasion during camp exercises, cursing Ted White while I stood my troop ‘to’ in the middle of the night waiting for an attack from ‘enemy’ around the perimeter. An attack that often never came. In 1915 the British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote: As a Commanding Officer, Ted White was never reckless — but the quote suits him well. He exhibited dare-devilry and cunning in his conduct as a soldier and as a Commanding Officer of his Regiment, these perhaps tinged with more than just a touch of the Australian larrikin. Such characteristics, together with the scope of his service, have earned him a memorable place in the history of the 10th Light Horse Regiment. Barry Bamford |

With the rapid change in vehicle establishment, most Junior Officers and Senior NCO’s in the Regiment were required to obtain detailed knowledge of the new vehicles. Ted White was no exception and he completed a Ferret driving and servicing course and obtained a Ferret driver’s license soon after returning to Perth.

With the rapid change in vehicle establishment, most Junior Officers and Senior NCO’s in the Regiment were required to obtain detailed knowledge of the new vehicles. Ted White was no exception and he completed a Ferret driving and servicing course and obtained a Ferret driver’s license soon after returning to Perth. Two years later, when Lt-Colonel Stock left to assume higher command in the Task Force, Ted White, now a fully qualified Lieutenant-Colonel, assumed command of the 10th Light Horse Regiment.

Two years later, when Lt-Colonel Stock left to assume higher command in the Task Force, Ted White, now a fully qualified Lieutenant-Colonel, assumed command of the 10th Light Horse Regiment.